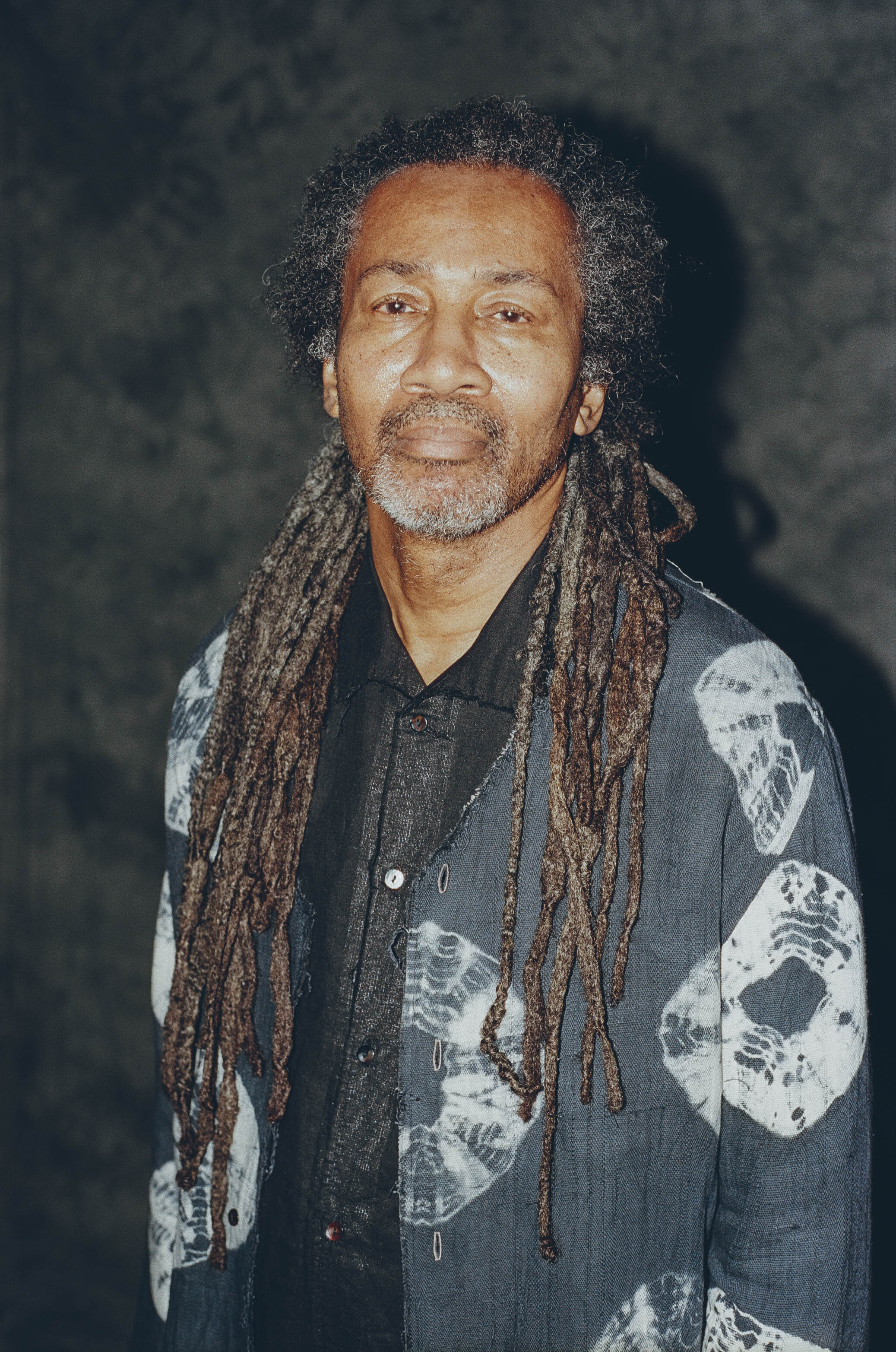

INTERVIEW : MONAD

There were times when you would walk down some England streets and see the postman, the dustman and any other blue-collar jobber wear the three-piece suit as an everyday uniform. Not the sharp and tidy type that’s now worn by corporate city boys, but the kind that was made in heavy wool, corduroy, thick cotton, in something that’d last the test of hard labour. That of course has changed: these days the most universal piece of workwear pretty much comes down to a pair of Carhartts (O.K., that and anything hi-vis). Yet whether out of nostalgia or novelty, it’s this very sense of utilitarianism that appeals to Nigeria born, London-based Daniel Olatunji, the designer behind Monad /

His take on workwear isn’t literal, but rather built on “familiarity,” says Daniel, “all while having a little something off about it.” In essence, the designer does tailoring that’s functional and thorough, only that there’s a feel of lived-in to the pieces. The first capsule collection he’s done that would go on to launch Monad altogether, which was commissioned by the team at Shoreditch concept store Blue Mountain School’s Hostem, had set the tone of the brand’s aesthetic: the blazer and pants made of Japanese linen were dyed twice, so that they appeared less new, their cuffs still had hanging yarns.

While subtly worn out, Daniel’s designs are extremely detail-oriented and well thought through, and that’s something that goes back to his years studying menswear at Central Saint Martins, where he’d spent “ages trying to properly press the pleats of a dress shirt,” he remembers, before moving on to some other assignments. Perhaps it’s this struggle to keep up with tight deadlines that accounts to his conviction to do what he knew was right: slow fashion. Turns out, it was more like a conscious decision. “Those little details mattered to me more than doing as many design variations as possible,” he tells us.

This focused, disciplined approach to design has stayed with him ever since. In fact, the styles he’s done in one collection tend to reappear in the following ones, with a few tweaks, of course, such as different fabrics, colours, and buttons, but as for their construction, it remains the same. The Wysman blazer — named after Blue Mountain School’s general manager Alex Wysman — serves as proof. To this day it’s been made in Japanese linen (as mentioned already, for the store’s capsule) and in handwoven cotton and other types of linen. And even if the silhouette technically hadn’t changed, from season to season they do look different.

“The same piece won’t look exactly the same depending on whether it’s made in wool or something lighter for spring and summer. It changes the look and feel because each fabric drapes differently”

“Textile pretty much is the starting point for everything I do,” he continues. The Wysman handwoven cotton version, for one, was weaved by artisans in Kano in north Nigeria and dyed at the Kofar Mata dye pits, using the same slow, natural technique that’s been passed down through the centuries. That’s to say, to him, the fabrics themselves become a source of inspiration when it comes to telling stories.

To source his other textiles, Daniel frequently visits warehouses to see if they received any further deadstock and surplus fabric rolls. He’s also in touch with an antique dealer that will send photos his way if they spot vintage fabrics they think he might be interested in. Once he finds something to his liking, then the designer goes about doing creative, curiosity-driven research about that fabric’s heritage— similar to what he’s done with the Nigerian cotton.

Upon doing some research for his latest collection, he visited a textile artist in Bradford who showed him around and gave him a glimpse into the area’s history. He then came across street photographs that John Bulmer and Chris Killip captured of the north of England working class in the 70s and 80s. In these photos people predominantly wore all-tweed-everything ensembles, but what stood out to Daniel was the attire that most women had: a floral apron. Ends up, the warehouses he went to were loaded with flowery viscose fabrics. “They probably can’t get rid of them,” he cracks.

“What I found interesting and ironic though is how women would protect their clothes with such a decorative pattern, only for it to be soiled with dust etc,” he remarks. “For them, the floral apron was their chore jacket.” Seeing a new light into the fabric’s past and a sense of purpose from it, he’s included in the collection overdyed, less vibrant than usual floral babushkas and lining for the blazers and jackets. The other fabrics he worked with were just as meticulously researched; the traditional heavyweight wools were sourced from north of England mills, and the Donegal tweeds were handwoven in Ireland by Eddie Doherty, one of a very small handful of artisans who still do it the old-fashioned way.

By making references to yesterday’s work attire, this is precisely what Daniel wanted: for people to make the most of their clothes and not be too concerned about whether they get worn out through time. Indeed Monad clothes are sophisticated compared to what’s on offer in mainstream fashion, in that it’s handmade and unhurried, and for the most part crafted out of handwoven, natural materials. But then again, what’s the point if people are not wearing it?

Referring back to the blue-collar job uniform of the old days, the three-piece suit, there was this idea “of looking somehow dressed up, with tailored clothes” Daniel says, “but they’d wear it to actually do stuff and that, for the years to come.”